Tip of the Week 2016-02-9 Wind Direction and Photographing Birds

When photographing birds in flight the most important consideration is the direction of the wind. Due to the need for the maximum amount of lift, birds nearly always land and take off into the wind.

Osprey in Silhouette

When photographing birds in flight the most important consideration is the direction of the wind. Due to the need for the maximum amount of lift, birds nearly always land and take off into the wind. For the shot above, the situation was as shown below, with the wind blowing into the sun.

Back Lit, Wind blowing into the direction of the sun

For this shot the wind was blowing as below to achieve a front lit shot.

Front Lit, wind blowing from the direction of the sun

Of course, most of the time the wind is not blowing either directly into or away from the sun. in this case to get a good shot you position yourself so that the bird is not directly flying into or away from the camera as below.

Osprey Landing on the Nest

Finally not only the direction but the speed of the wind plays a factor On very windy days the speed of taking off and landing is much slower, and predictable than on calmer days. Therefore I get a much higher keeper rate on windy days.

On my photo tours when planning the morning's or afternoon shoot when planning on photographing birds in flight, I always check the weather report and check the direction and speed of the wind and plan accordingly.

Tip of the Week 2016-02-2 Close up photography with a 50mm lens

Last week I wrote on the virtues of a 50mm prime lens. This is one more trick using that lens. By reversing the lens using an adapter, you can focus very close to a subject and magnify the image significanly.

Macro Shot with a Reversed 50mm Lens

Last week I wrote on the virtues of a 50mm prime lens. This is one more trick using that lens. By reversing the lens using an adapter, you can focus very close to a subject and magnify the image significanly. By reversing my 50mm lens I can focus at about 3 inches rather than the 16 inches mounted in the normal position. measuring the magnification, I can achieve nearly 1:1 manification rather than 1:7. While not of the quality of my macro lens, as seen in the image above, quality is quite good. In my case it enables me to carry a small adapter on a trip and shoot macro subjects without carrying the large macro lens. For others, it's an inexpensive effective way to get into macro photography. I purchased my adapter on Amazon and this is the one I got. A nice feature of this adapter is that it not only has the lens adapter to mount to the camera, it also attaches to the lens mount and allows you to control the aperture. For those of you with lenses without aperture control (the ones that work on Nikon consure DSLR's), it allows you to adjust the aperture.

While this adapter is for Nikon Camera's with lenses having 52mm filter threads. There adapters for many different camera brands and lenses so make sure what you get works with your camera and lens.

Tip of the Week 2016-01-26 The Virtues of the 50mm Lens

The 50mm f\1.8 lens was the kit SLR camera lens until the late 1990's until it was displaced by the variable aperture mid range zoom lens. In many ways this was an unfortunate change.

The 50mm f\1.8 lens was the kit SLR camera lens until the late 1990's until it was displaced by the variable aperture mid range zoom lens. In many ways this was an unfortunate change.

Yes, it is convenient to be able to stand in one place and twist the zoom ring and compose a picture the way you want it. However the typical kit lens is:

- Of doubious quality. While high end zoom lenses rival if not equal prime lenses, inexpensive zoom lenses do not. Close inspection of the images they produce will show the imperfections in these lenses.

- Not a very fast lens. This not only means you don't get as good of low light performance, more importantly you are not able to limit the depth of field by selecting a wide aperture and letting the background of your image blurr.

- Larger and heavier then a 50mm lens

On full frame camera's 50mm's is considered the normal focal length, closely approximating your eye's normal field of vision. On a crop sensor camera it is a moderate telephoto lens, ideally suited for portrait photography.

If just starting out, I'd suggest purchasing a camera with a 50mm lens rather than the kit lens, or purchasing a 50mm lens as your first additional lens. All the major camera companies offer inexpensive 50mm lenses, these tend to be of very good optical quality and perform very well compared to the camera's kit lens. Many professional photographers carry a 50mm lens in their bag as it is small, light, and excellent optically.

When purchasing your lens, make sure you're getting one compatible with your camera. The less expensive DSLR's often do not have a built in focusing motor, so if you want autofocus you'll want a lens with the focus motor built in. In addition, there may be limitations with the camera meter with the older style lenses, make sure you do your homework and purchase a lens compatible with your camera.

Tip of the Week 2016-01-19 Manual Focus Nikon Lenses

One of the main reasons I never switched from Nikon to Canon was the fact that Nikon has never changed its lens mount from the F camera in 1959 until today. [Several years ago Nikon published a list of their current lenses which would make the most of the then new D800E cameras][0]. The list was small and with very few exceptions the lenses on the list where very expensive. I own several of those lenses, and they are indeed fine lenses.

However for some types of photography, older Nikon Manual Focus lenses may be a better choice.

24mm, 50mm, & 105mm Nikon Manual Focus Lenses

One of the main reasons I never switched from Nikon to Canon was the fact that Nikon has never changed its lens mount from the F camera in 1959 until today. Several years ago Nikon published a list of their current lenses which would make the most of the then new D800E cameras. The list was small and with very few exceptions the lenses on the list where very expensive. I own several of those lenses, and they are indeed fine lenses.

However for some types of photography, older Nikon Manual Focus lenses may be a better choice.

- The focus mechanism is better on these lenses than the manual focus control for autofocus lenses. So if you're going to be manually focusing for landscape, macro, or product photography, you will get better results.

- These lenses have a depth of field scale, simplifying setting the proper focus distance particularly when photographing landscapes.

- Without the complex mechanical and electronic parts required for autofocus and Vibration Reduction technologies these lenses tend to be more reliable and cost much less to repair. In fact I've had more difficulty getting my newer autofocus lenses repaired and in two cases fairly new lenses were returned by Nikon stating that parts were no longer available.

- Many of these fine lenses can be purchased in very good condition at very low prices compared to the current lenses offered by Nikon.

Depth of Field Scale on my 40 year old 24mm lens

There are a couple of things to be aware of.

- Only the higher end Nikon Digital Cameras will support metering (check prior to purchasing) without a modification to the lens to add a cpu chip and contacts. This is something I have not tried so can't personally recommend at this time.

- Lenses made prior to 1977, known as non-AI lenses, need to be modified prior to mounting on your camera as damage may result. The modification is easy to perform yourself and there are several people performing this service for a reasonable charge. But don't mount the lens without doing the mod.

- While this article is for Nikon users, some people are adding an adapter to mounnt these lenses on Canon and Sony cameras with good success. You may want to check out your options for this.

Links

Tip of the Week 2016-01-12 Sunny 16

The image above is of the camera I used from about 1969 until 1980. It's a Yashica 635 Twin Lens Reflex camera and it took great photographs. One thing missing from it and most cameras of its day was a light meter. While I had an external meter, it was marginal at best and most of the time I used no meter even though I shot mainly slide film which had very little exposure latitude.

Funny thing, most of the time the exposures were dead on. Back then when you bought a roll of film it came with a sheet of paper instructing you on how to set your camera to get the right exposure. Looking at the paper carefully it always said to set it in bright sunlight for f\16 and the reciprical of the iso speed of the film. So if shooting 100 iso film the paper said set it to f\16 at 1/125th (the standard speed) of a second. You could modify that at the equivalent settings of f\11 at 1/250th, f\8 at 1/500th, etc. It also said what to do in other conditions, add one stop of exposure for hazy sun, two for overcast, etc. Believe it or not, it worked very well. This is called using sunny 16 exposure.

What does it have to do with today with our super sophisticated matrix / evaluative metering beauties that seem to do everything by themselves. Actually quite a lot.

First if you believe in using standby settings, and you should, it is easy to estimate what approximate exposure you'll be needing and preset your iso settings to make sure you have a fast enough shutter speed for the aperture you think you will need to get the appropriate depth of field. So for example if I'm photographing Osprey in flight and it's mid-morning with bright sun, I know I want about f\8 to keep the face of the bird sharp and I want a shutter speed over 1/1000, so knowing I'm two stops faster than sunny 16, ISO 100 would be 1/400 and ISO 200 would be 1/800, I'd select ISO 400 and expect a shutter speed of around 1/1600. In fact I may manually select that and then check the histogram periodically so verify that's correct.

Also, believe it or not, sometimes our fancy meters are simply wrong. As you're shooting, if you notice the metering doesn't match what you would expect from the sunny 16 rule, it's time to start checking things to see if they're right. I had a problem several years ago with a lens aperture sticking and not closing down to the f\11 aperture I had selected. The shutter speed ended up being much faster than I expected and I was able to sort out what was wrong and change to another lens and get the shot. If I'd just trusted the meter. the depth of field would have been unacceptable. Often the meter guesses wrong, or you've forgotten to take off exposure compenstation or bracketing and you may miss the shot of a lifetime.

So spend some time and learn how to use Sunny 16 and you'll thank yourself for it.

Tip of the Week 2016-01-5

This week's tip of the week is to use standby settings to reduce the chance of missing a shot.

If, like me, you've missed shots because you're in the wtong metering mode, have exposure compenstation set, you're in the wrong auto focus mode, have bracketing set, etc., you may want to have some standby settings you set your camera to when not in use.

Get into the habit of putting your camera into these settings when you're through shooting and then double checking when you start shooting.

You may also want to think through before a shoot, what settings you're liking to need in your camera and replace your standby settings with those.

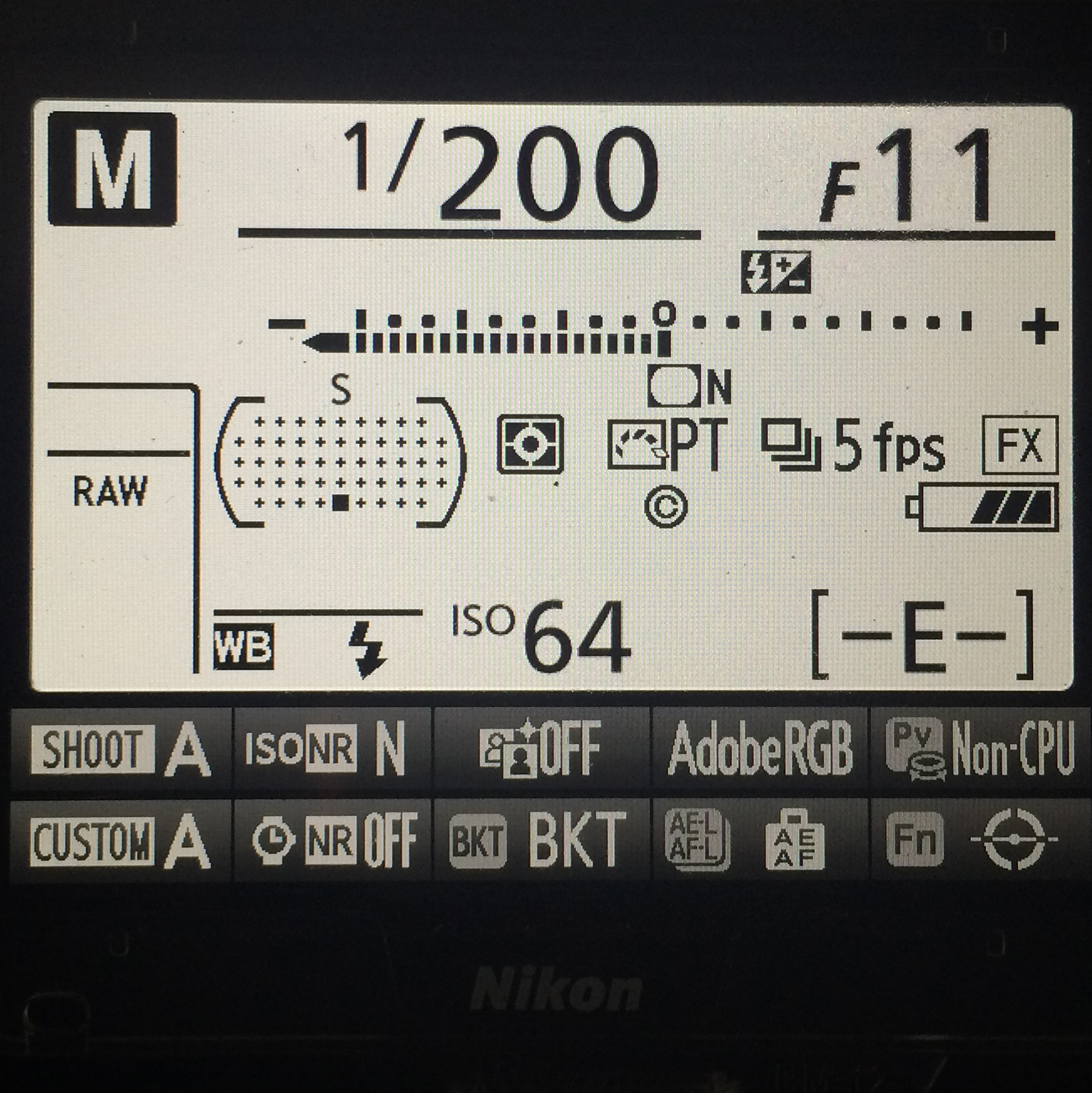

Many of the newer cameras have a info screen which nicely summarizes what you have set. Get used to looking at this to doulbe check your standby settings.

Particularly when you're shooting action, having the camera preset, could be the difference between getting a killer shot or none at all.

Nikon D810 Info Screen

Tips of the Week 2015-12-29 Focus Stacking Extending the depth of field

This weeks tip of the week examines focus stacking to extend the range of sharpness of an image.

Toy Ducks Photographed using focus stacking

Last week I covered shooting in the same focal plane to allow making a sharp image of multiple or large objects. This week I offer a work around where that is not possible or desireable.

The shot above is a similar shot to last weeks. As before the front duck is closer to the camera than the rear one. As you can see below, without focus stacking, the rear duck does not appear sharp, particularily on its' back. At larger sizes the whole duck appears soft. The camera is 3 feet away from the nearest duck and is set at f\11. Looking at a depth of field chart, depth of field is approximately 1 inch and from the front of the first duck to the furthers point on the second duck is about 4 inches.

Toy Duck photographed without focus stacking

Focus stacking is accomplished by taking multiple shots at varying focus points and then using software in post processing to form a composite image with the sharpest selections displayed.

For this photograph, I did 4 shots, manually focusing from just behind the front of the first duck to just in front of the rear of the second.

There are several options to make the stack. The frist is to use photoshop. To do this you open each image on a layer of the same file then select all of the layers and under the edit menu select auto align layers. After that task is complete, select auto blend layers from the edit menu. For most simple situations, such as this one, this works quite well.

For more complex projects, there are several good tools available. The one I use is Zerene Stacker which does a very good job and has a very good editing feature that allows you to touch up problem spots.

Focus Stacks can also work well for landscape photography, with a couple of limitations.

The scene below is similar to one featured several weeks ago. Except in this case I used a 50mm lens set at f\11. The Hyperfocal distance in this case is around 60 feet, set there things will appear sharp from about 30 to infinity. The Spanish Moss in the foreground is about 7 feet away. Clearly this is not going to yield a sharp image. Again I used focus stacking, five shots, manually focused from the foreground to the background, and merged them with Zerene Stacker.

As I mentioned before there are a couple of serious limitation with this technique.

- I doesn't work with objects that are moving. In this scene here there was a pesky squirell that showed up in two places and had to be cloned out. With major amounts of movement the images simply will not properly align.

- Exposure must remain constant. Passing clouds will really mess up the results.

- Both the shoot itself and the post processing is time consuming.

However, in many cases the technique works quite well and enables getting a good shot which seems impossible.

Tip of the Week 2015-12-22

Aligning the focal plane to make sure what you want sharp is sharp.

White Peacock Butterfly - Butterfly Place Westford, MA

This week's tip is to keep those things you want to appear to be sharp in the same focal plane. The shot of the butterfly above is an example. Taken with a 200mm macro lens at a wide aperture to render the background soft and to emphasize the butterfly, I carefully positioned the camera to keep the wings sharp. Even so, the very tips of the wings are a bit soft. The choice would have been to select a smaller aperture to give a greater depth of field, however doing so would have destroyed the soft background I wanted for the shot.

Another example below was set up to show the difference. I used a 100mm lens at about 5 feet from the toy ducks. The first image was set up with the eyes of the ducks in the same plane and the front of both of the ducks appear sharp. The second was set up with one duck closer than the other in a different focal plane. One is sharp and the other is clearly not.

Therefore when shooting with a narrow depth of field, such as a macro shot or using a long telephoto lens, carefully position yourself to maintain the parts of the image you want sharp in the same focal plane.

Tip of the Week 2015-12-14 Using Hyperlocal Distance

How to make an image sharp from edge to edge. Hyperlocal distance and the proper focal length.

Mandalay National Wildlife Refuge–Nature Trail

This was taken on a walk last week. I wanted to record the trail with detail from foreground to background. The easiest way to accomplish this is to select a focal length with sufficient dept of field and to focus at the point called the hyperfocal distance. This is the point where you have the greatest depth of field from infinity.

Depth of field is greatest when using a wide focal length and the smallest possible aperture. However, if you select the smallest possible aperture you image won't be as sharp due to something called diffraction. Normally I try to keep my aperture no smaller than f\11 to minimize this effect.

With older prime lenses this is easy. They have a scale on the focus ring and you simply put the infinity mark on the line for the aperture you select and you can read the close focus distance on the other end of the scale on the corresponding mark. Due to the extreme resoluting of my D810, I hedge a bit and pick one stop larger aperture. My 24mm lens was ideal in this case, set for f/8 the hyperfocal distance is about 7 feet and everything should appear sharp from 4 feet to infinity. I set the lens and stopped down an additional stop to f\11. I'm using a manual focus lens, but if you're using an autofocus lenses be sure and put it into manual focus so you'll retain your setting.

For newer lenses without a depth of field scale, you can achieve the same result using a Depth of Field application on your phone such as TrueDof-Pro which can be found here. This app has several advantage including taking diffraction into accounsst. The link also includes a very good more detailed explanation of Hyperfocal Distance, Depth of Field, and Diffraction.

In addition, you may find the distance scale on newer lenses is not accurate enough to make the setting (or it doesn't have a scale at all). In that case, put you camera or lens into manual focus and pick an object at approximately the correct distance and focus in the viewfinder before taking the shot.

Below are two close up crops from the both ends of the trail.

The beginning of the trail

The end of the trail

Tip of the Week 2015-12-7 Blurring the Background

A how-to article on how to make an image pop by blurring the background.

White Faced Ibis, Blurred Background

The image shown above was taken with a 70-200 mm lens with a 2x teleconverter at an effective focal lenght of 380mm. An Aperture of f8 was chosen to insure the face and body of the bird appeared sharp and to provide a pleasing background.

Depth of field, or the portions of the image that appears sharp, is a function of distance, focal length, and Aperture. Distance and focal length also determines the size of the subject in the frame, leaving the aperture as the determing factor for how sharp or blurred the background appears. I like the look of this images as the background appears as out of focus spots of color, drawing attention to the sharp part of the image, the bird. There is no doubt that it is the subject.

Red Winged Blackbird

This image was taken with my 600mm lens with a 1.4X Teleconverter. It was taken with the Aperture set wide open at f5.6. In this case with the extreme focal length and wider Aperture, as well as the greater distance to the background, the background is completely blurred. Again the out of focus background draws attention to the bird.

In both of the cases the choice of lens used was due to the subject being photographed. In many cases, like when you're photographing people, you can choose to use a larger focal length lens with a wide aperture and move further from the subject giving you the creative control to draw attention to the subject. Such as this photograph of my Grand Daughter taken with a 200mm lens at f2.8

Lizzy at the Park

Tip of the Week 2015-11-30 Blurring the foreground

A how to article on making a background element pop, by blurring the foreground.

Fall Moon

A different twist on using selective focus to emphasize your subject. Try putting a distant object in focus with a much closer object out of focus to frame the subject. The key is to make sure there is a separation from the near to the far subject.

Depth of field is a function of focal length, distance, and aperture. By using a long focal length, a wide aperture, with objects separated by a large distance, you can create this effect.

Depth of field of my 600 mm lens at an aperture of f\4 focused at infinity is from about 2000 ft to infinity. So everying closer than that will be burred. The maple tree in the foreground was about 50 feet away so by carefully positing the camera I was able to create this nice framing effect suggesting the moon in the fall.

Tip of the Week 2015-11-24 Fog and Depth of Field

A how to article on photographing landscapes in the fog. Focus on the foreground!

Foggy Morning Lake Martin

This image was taken with my 28-70mm lens set at 70mm. The branches in the foreground were about 6 feet away. A quick look at a Depth of Field chart would show that it is impossible to get both the foreground branches and the trees in the background clearly in focus.

However, even if the background were in focus, the fog would make the trees appear blurry. In this case, the best proceedure is to do as I did here, stop the lens down, I used f22, focus just behind the branches, I used about 10 feet, and let the background be out of focus. The branhes appear very sharp and the background appears naturally blurred.

Use Tonal Contrast to Emphasize Your Subject

A how to article on making an image pop with contrasting the subject with the background, Light on Dark, or Dark on Light.

Snowy Egret, dark background

Good photography tells a story, you want the viewer of your photograph to immediately understand what that story is. There are visual tricks to pull that off. One of the best is to use contrast to draw the viewers eye to the subject. The image shown above is an example. The white egret is immediately the subject against the dark background.

To accomplish this, first you need to isolate the subject against a dark background. Often, as in this example, the way to do this is photography the subject in bright sunlight against a background in shadow.

One tricky thing about this is that it nearly always fools your camera's meter. If you shoot in an automatic mode, the dark background will be rendered lighter as well as the light subject, often burning out the details. Judicous use of negative exposure compensation or as I do, manually metering using a spot meter on the bright subject and adding about 2 stops of light, is required to get things right.

Below is an example of a dark subject against a light background. The same visual cues are involved. Again, exposure can become a challenge. I metered on the cat and subtracted 2 stops.

Keeping this in mind as you work your subject will improve your ability to make your subject stand out in a scene.

Simon

Work Your Subject

Rose Macro Shot

This weeks tip of the week is to work your subject.

The image pictured here is a rose taken in my front yard. The rose is about the size of a dime, very small. I was out shooting and noticed the roses in bloom. I had a 200mm macro lens on the camera, which only magnifies to a 1 to 2 ratio. Taking several shots didn't do it for me, I went in the house and brought out my 105 which went 1 to 1, better but still not great. I added an extension tube, and liked what I saw.

I then brought the card from the camera inside and put it in the computer. It wasn't sharp from one side to the other. I repositioned so the rose was in the same plane as the camera and stopped the lens down as far as it could go, again checking the camera, I have what you see here.

I spent well over an hour working on the shot, often your best results are from repeated efforts to get things right

To learn how to make this kind of shot, I'm teaching a macro photography course On December 4th, 2015 check it out here.

Preventing a Common Lens Failure

Tip of the Week 2015-11-1

Storing your lenses

Having a working lens when you go out to shoot is obviously critical to your success as a photographer. Having two failures last year due to a sticking aperture led to a bit of research on the web. The problem is that when you stop down the lens and take a shot, the aperture stays open instead of shutting down to the proper setting leading to badly overexposed shots. This is caused by lubricant seeping onto the aperture blades from the manual focus helicoil.

There are several things you can do to reduce the risk of this occurring. First do not store you lens with the front facing down, if the lubricant does seep with the fromt down it will seep into the aperture blades, facing up it will not. Second avoid placing your lenses in hot places, like the trunk of a car on a hot day. I believe this is what caused my two lenes to fail last year.